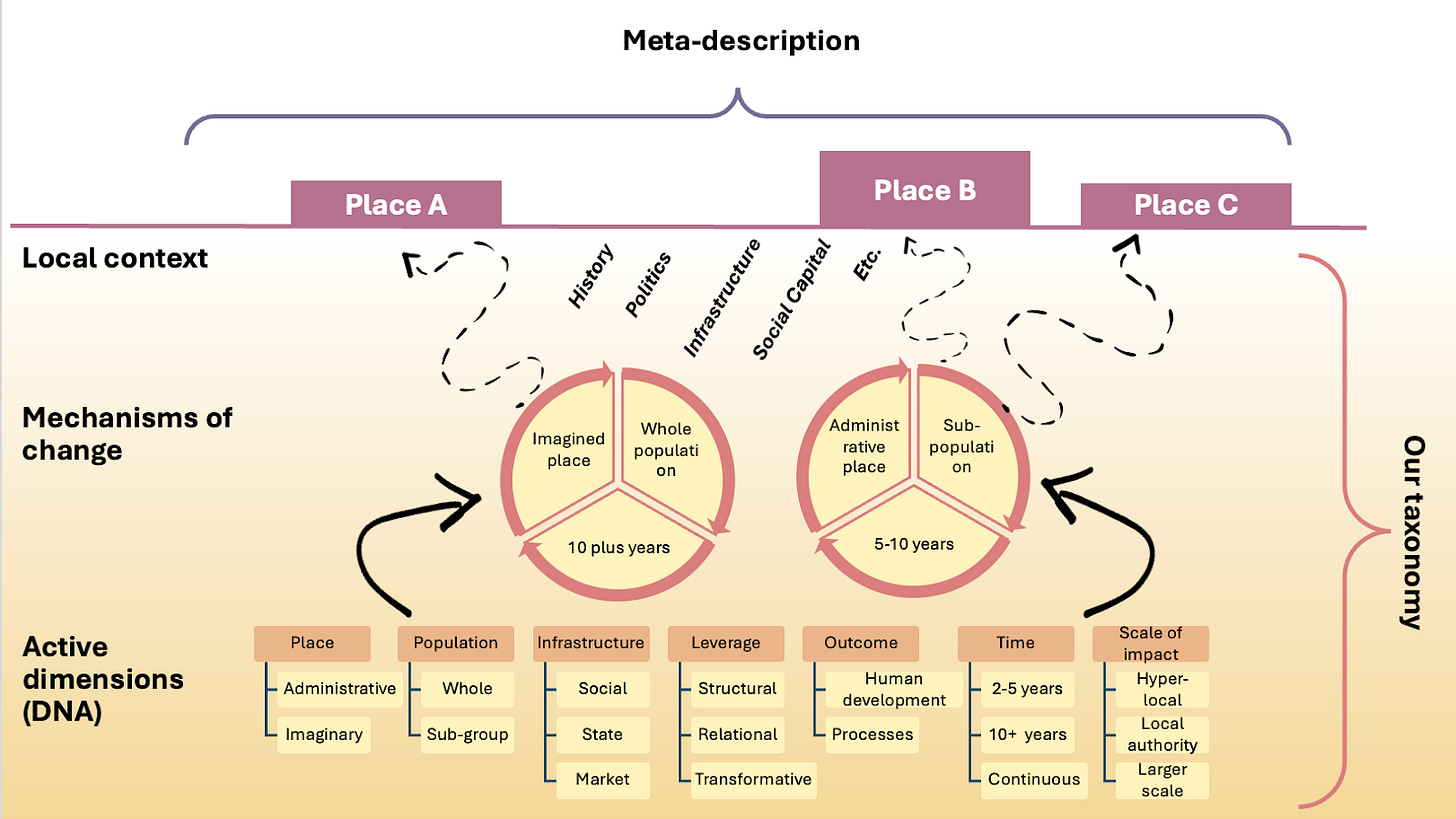

In the previous post, we described the seven dimensions we used to analyse similarities and differences in place-based change. When we examined the literature on dozens of placed-based projects, multiple mechanisms emerged.

In the next set of posts we will describe what think might be the five primary categories of mechanisms of change, but in this one, we want to first illustrate how the dimensions helped us understand how change is realised in place.

In the table, we summarise two place-based projects. The first will be familiar to funders and leaders of civil society organisations working alongside local people. The work is hyperlocal, concentrated on residents who feel connected by the estate in which they live. The work focuses on everyone, although not everyone participates. The focus is on the social infrastructure of the estate, and the goal is to improve existing and create more opportunities for residents to connect. Any benefits to health and happiness are welcome but seldom feature in the planning of the work. The levers for change are all relational. The work is viewed as long-term, not hindered by the vicissitudes of funding.

The second project will be familiar to change makers in government. The scope of the work is wider, covering an entire local authority. The focus is narrower. It aims to encourage those not involved in sport and leisure to be more physically active. The levers of change are structural, encouraging services to refer residents to relevant resources. Building community around those who participate is part of the strategy. The work is instrumental. It measures impact in terms of reductions in long term conditions like obesity. It is underpinned by a national funding programme that supports similar efforts around the country.

Both of these examples can legitimately be described as place-based change. But they operate radically different mechanisms of change and seek significantly different outcomes. It follows that the need for evidence will also differ.

When comparing our approach to the dimensions we described in a previous post, you can see that we are using the dimensions to create the mechanisms. Each place can use multiple mechanisms in its work, (it is likely to prioritise one or two), and each place pulls that mechanism through the particularities of their local context. That process of contextualising and delivering in a place is what makes it unique. But the mechanisms, of which there can be many, are what begin to define a field of practice. This is really important to stress - no organisation or place is entirely defined by a mechanism, and they will always have their particularlities and uniqueness. But they are likely to prioritise something in terms of how they achieve change. Throughout the next few posts we will use examples to illustrate mechanisms, but we are not trying to simplify or flatten local practice, we are trying to get to the right level of generalisation.

The following five posts set out our broad five categories of mechanisms that have emerged from our analysis of practice. There are likely many more mechanisms than those we have identified, but we think our categories hold and are useful.